Our islands close this year on a somber note. With the Pacific Ocean still roiling, heavy La Niña rains nearing, rampant political unaccountability, and embezzlement and malversation of public infrastructure funds, danger, anger, sadness, and fear mark a very un-festive holiday season. Here is to a new year and a new dawn for our tropical islands, whose tropicalities have long been the pulse to our writing and phenomenalities, including not only these poems by Charlie S. Veric but also Doreen Fernandez and Ed Alegre’s Sarap and Palayok, with their silver-gray shrimps leaping in a basket, and the concept of the island paradise in the sketches of this issue’s featured artist, Kitty Taniguchi.

—Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz, Editor

Following my return from Stellenbosch, I went to Dumaguete in the summer of 2024 to visit the archives at Silliman. After spending a week looking at dusty documents, I crossed into Siquijor. Alone in the resort where my room opened onto a view of the open sea, I started the first few poems for what I thought would be my sixth book of poetry.

In Stellenbosch, I had been awed by the otherworldly landscape of wine farms and snow-capped mountains where the winds blew hard at night. I also witnessed progressive politics that coexisted with the hardy remains of the apartheid. It was there that the idea for my new book came to me. How does one reimagine the world radically? Watching the tide come and go, I started writing the first few poems. Before my vacation was over, I drafted around thirteen fragments. Since returning from Siquijor that summer, however, I haven’t gotten around to writing another poem. Mundane tasks took over. I had to put the sixth poetry book on the back burner—perhaps to let it simmer until the urge to write claims me once more.

—Charlie Samuya Veric

Charlie S. Veric holds a PhD in American Studies from Yale University where he was awarded the John Hay Whitney Fellowship. A former fellow of the Johannesburg Institute for Advanced Study and the bestselling author of prose and poetry works including Histories, Boyhood, and The Love of a Certain Age. An Associate Professor of English at the Ateneo de Manila University, Veric’s academic scholarship includes Children of the Postcolony (2020), which reconstructs the foundations of Filipino postcolonial thought.

What, for you, is the link between politics and landscape?

Landscape constitutes my poetry. My poetry books are defined by the places where they were first conceived and completed. When I write, I have to be in a particular place. In The Love of a Certain Age, I wrote in a condo and had to be in spots where I got the frenetic energy I needed. No Country was shaped by my experiences in Johannesburg where I was mugged in my first week soon after my arrival, and yet it was also a place that allowed me to see an alternative future. Songs from Manunggul was written both in the city and the countryside; as a result, the structure of the book reflects this character. Whatever politics may be gleaned from my books would have its origins in the places where they were written. But politics is embedded. I let it disappear in imagery. The image becomes politics manifested.

Do you have any personal rituals associated with your writing; what are they?

The only ritual I have to satisfy when I write is loneliness. I have to be alone with myself, my feelings, my thoughts. I have to lose myself in my created world to begin to know that I have a poem to write. Without this immersion in loneliness, I cannot write.

Cristina “Kitty” Taniguchi is a visual artist whose paintings and sculptures have been permanently installed in the new Ordos Park, Inner Mongolia, China, collected in the Beijing International Art Biennale, and recently exhibited at the Leon Gallery International in Manila, among many other venues. Kitty also occasionally writes about art and culture, in various fora, and published two poems in the Philippines Free Press. Educated at Silliman University in Mass Communication and English and American Literature, she presently lives in Dumaguete City where she runs the Mariyah Gallery.

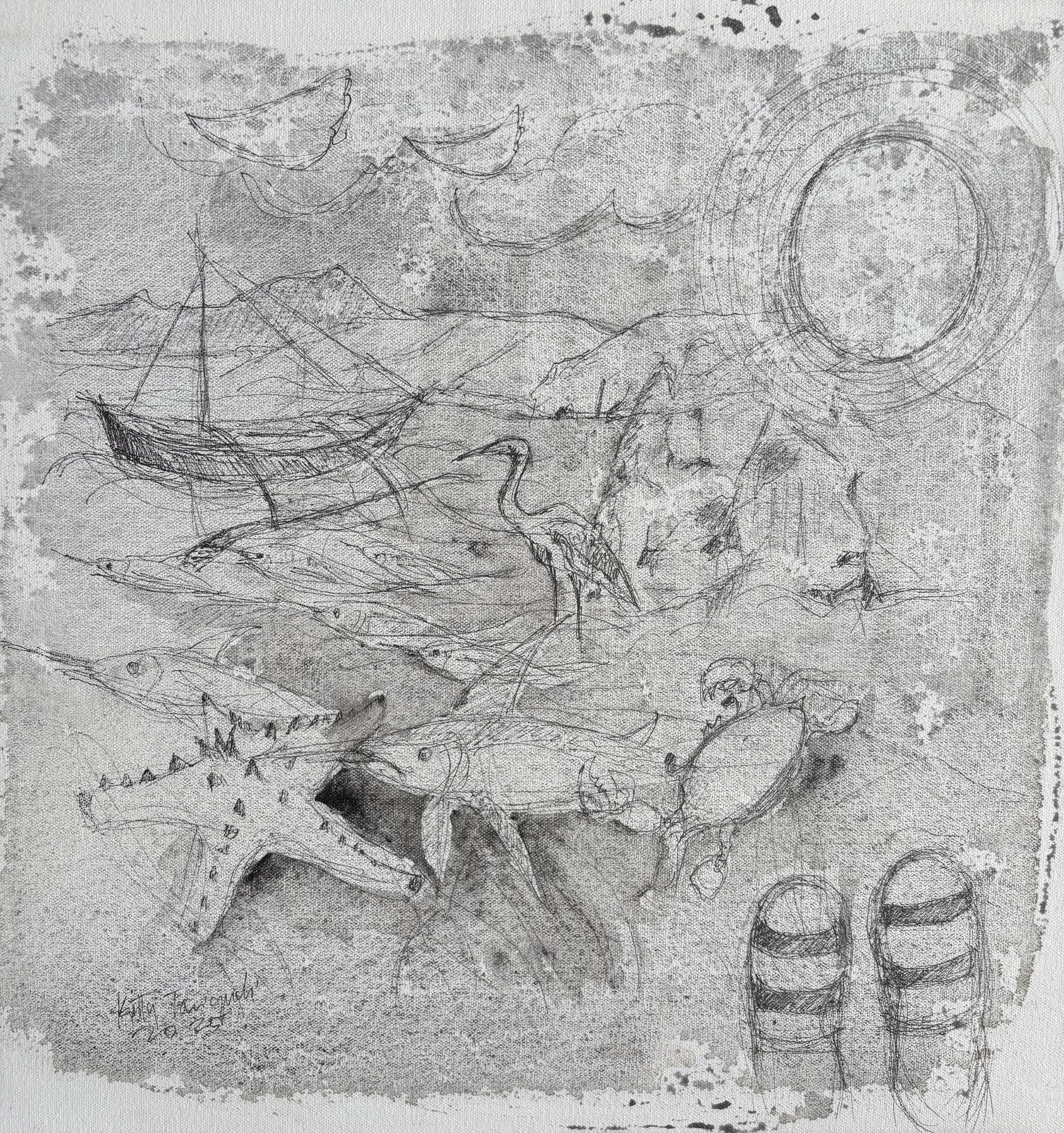

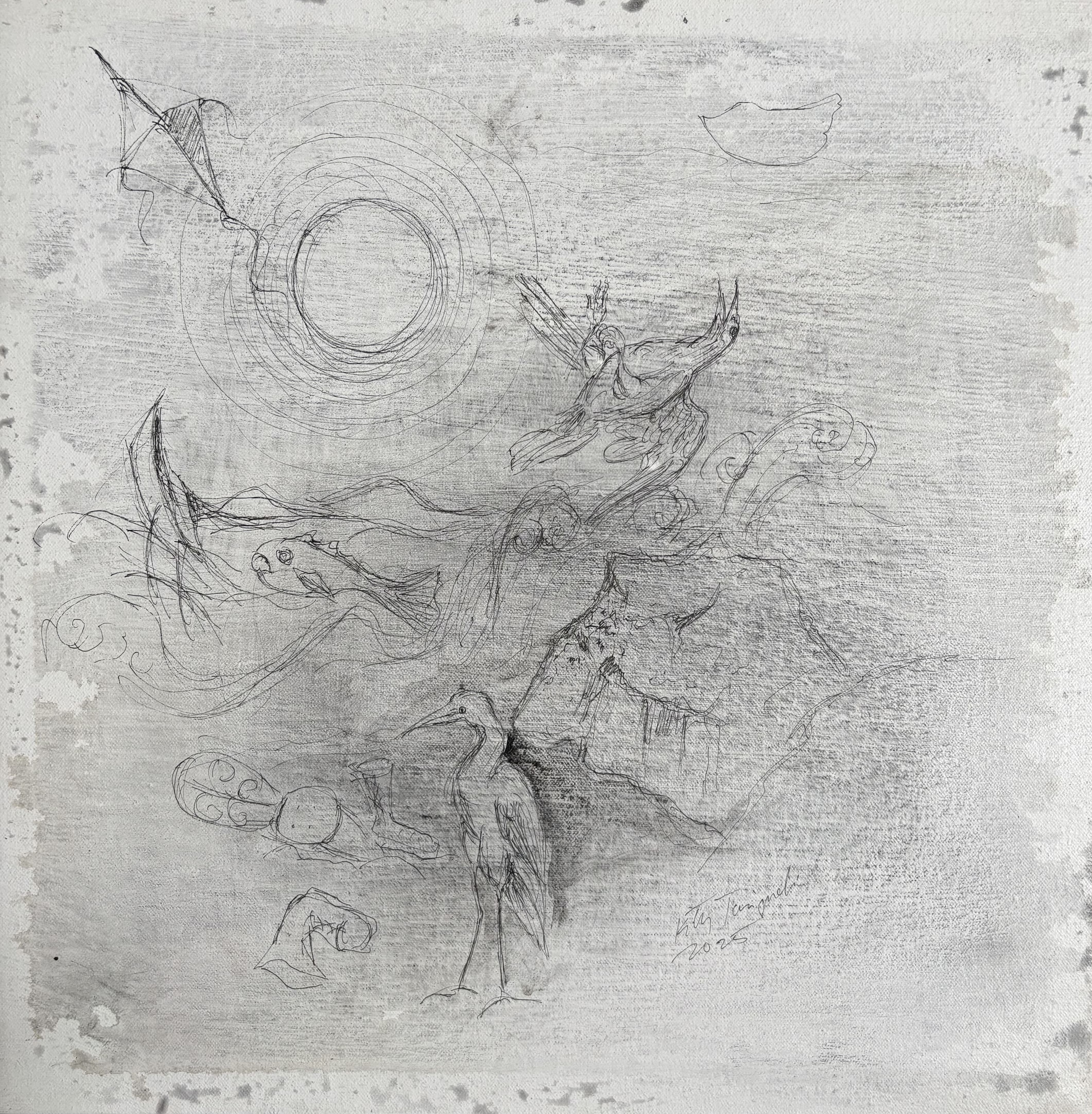

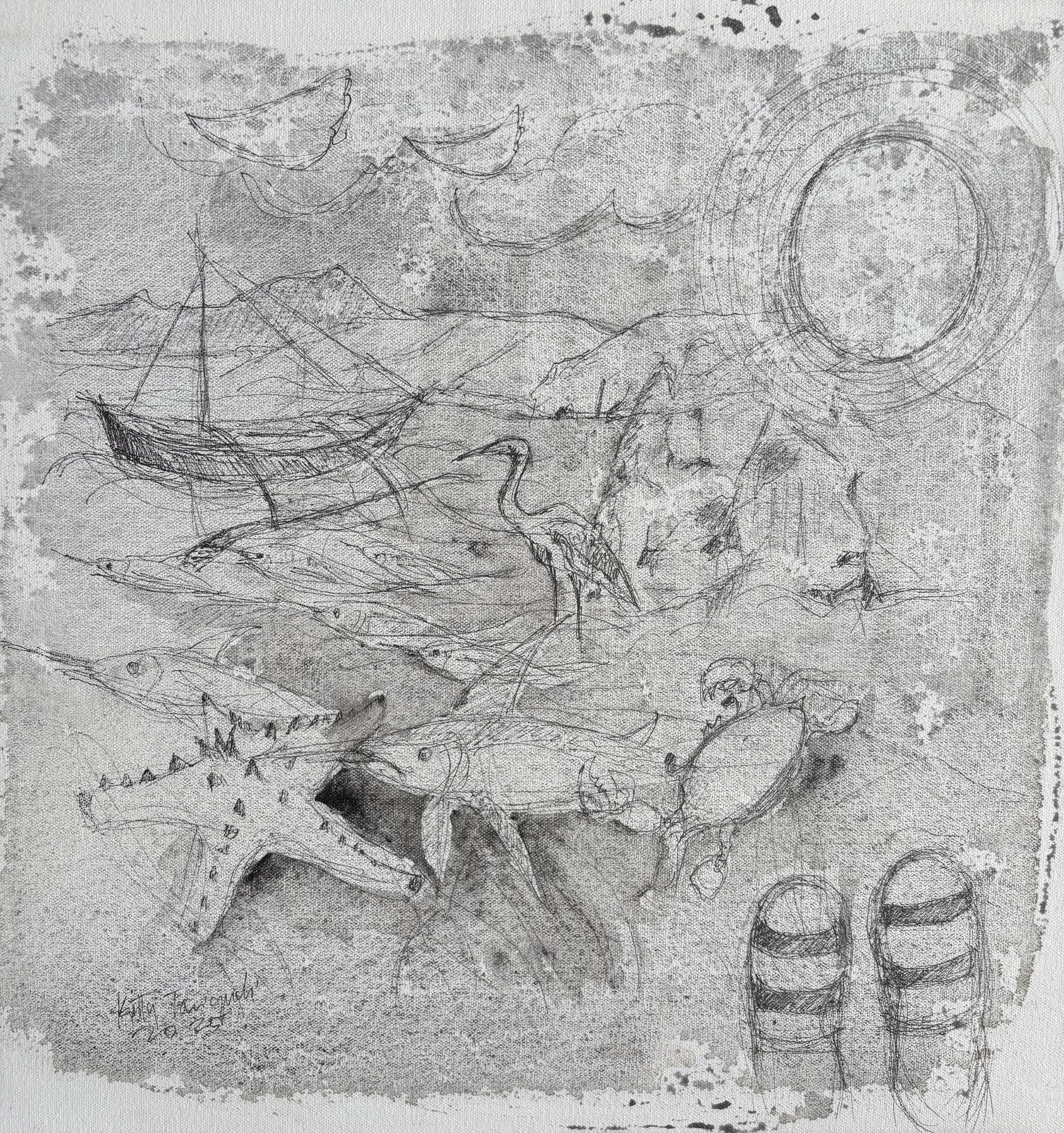

Your two drawings are clearly related, yet also seem like inverted lenses into one another, almost as if they are reflecting one another through a looking glass. Could you elaborate on their relationship to one another formally, topically, or in terms of their creation?

I was trying to reflect in my drawings Charlie Veric’s descriptions of Siquijor as he initially sees it: an island paradise. I was also trying to get to the bottom of his emotions as the poem progressed, as he delved into a kind of sadness (or, even anguish, or anger?) thinking about the terrible fate of people in contrast to the beauty of the island… of people who literally drowned during a deluge, or the madness of nature, and of people who died from war, or from atrocities of those who are in power.

I tried so much to be true in reflecting what I supposed in the poem, but I also couldn’t help thinking about the Siquijor that I knew in my childhood. I project my psyche as an artist, with the impulse to imagine further beyond reality. So, there. I couldn’t help but include a metaphorical crow—upside-down, as I love to do in some of my paintings—to talk to the egret, and to fly side by side with the kite…

Maybe, in this particular work, perhaps, this is the easiest way for me to reflect upon Veric’s melancholy? Or his want for “another world…”

As for the simply happier drawing, the crow is replaced with Siquijor's flying fish, starfish and crab… and yes, the heavy sandals—all reminders of a merrier time when children, as we, were unaffected in our little world, frolicking in the shallow parts of the water, admiring the pleasantness of being under what felt like magical clouds, meeting the sea farther in the horizon.

Much of your past work has dealt with femininity and gender, could you tell us more about your approach to the animal and the non-human, as seen in these two pieces?

There was a need for me, from a psychological level, to shift to another subject matter in 2020.

For a long time in my art career, I was owning a kind of genre, doing work on femininity and gender. I told myself one day that I had to let go of (for the meantime) my preoccupation with women. I am no exception from artists who have experienced the need to change. So, I started incorporating lions, cheetahs, crows, and mythical horses on large canvases minus the human figure.