“. . . [H]ands covering bleeding ears, backs that couldn’t flee from whippings, sexes shat on, necks strangled by ropes, noses long numbed by the smell of corpses rotting . . .” Alvin Yapan’s story is visceral, corporeal, sensorial even, and yet somehow amid such earthliness, the story is distinctly otherworldly. Yapan’s corporeality is a guide through reality, assuring the narrator and reader alike that something really is out there—that we really are here. This also relates to the sensorial “madness” of Wilfrido Nolledo’s But for the Lovers, which transcends linear temporality and which in its attempts to fix itself so solidly to the ground only floats further from it.

Perhaps this is also a productive way to discuss the act of translation itself, which this issue of e.g. journal centers. Christian Benitez’s English translation of Yapan’s original Tagalog work must safely transport a body from one world to another, maintaining its basic truth, effect, character, and integrity, while appearing in a form completely other but recognizably unitary. Czar Kristoff, who hails from Bicol and currently lives in Laguna, is this issue’s featured artist. His works hover over and between planes—lapping memory and portent, the unnatural and the quotidian. “He was beginning to eat flowers, and the crescent moon was in his eyes when he awoke again.” —Wilfrido D. Nolledo

—Nicole CuUnjieng Aboitiz, Editor

“Mga Alamat sa Bayan ng Sagrada” was a writing exercise that informed my approach for my first novel, Ang Sandali ng mga Mata. In this historical novel about three generations of the Nueva family in the Bicol region, I aimed to capture the sense and feeling of “epic time.” By “epic time,” I mean the sweeping narrative that spans significant periods, drawing parallels and highlighting repetitive patterns from pre-colonial Bikol to post-EDSA Manila. Given the scope of historical time and the parallels I aim to draw, I sought a strategy to balance the plot’s breadth with the psychological depth of the characters. I wanted readers to empathize with my characters despite the vast temporal distance covered in the narrative.

The narrative design draws on the Bikol epic Ibalon as a template for understanding the repetitive history of the Nueva family and the nation. In Ibalon, we hear the adventures of the three heroes, Baltog, Handiong, and Bantong, though their motivations and drives remain largely unexplored, which in the epic is inevitable and even necessary as they are Jungian vessels of a community’s value system. While my characters, Selya, Nene, and Boboy, correspond to these epic figures, I aimed to lend them psychological depth. This presented a challenge: reconciling the epic’s communal nature with the novel’s individualistic identity, a tension noted by György Lukács and Mikhail Bakhtin. However, Resil Mojares’s study of the Filipino novel suggests a continuous generic history between the epic and the novel in Philippine literature.

Given the project’s ambition, I began with a short story, “Mga Alamat sa Bayan ng Sagrada.” Writing this story led me to a synecdochic technique: using parts of the body as emotive links between characters across generations and worlds. The eyes of contemporary characters become the eyes of epic heroes; the tactile experiences of the legs and feet of mothers are repeated in their daughters. I rehashed some portions of this short story in “Ang Ulan ng mga Bala,” chapter 10 of Ang Sandali ng mga Mata. This technique, relying on metonymic links rather than metaphors, which would sometimes deteriorate into analogies and symbolic representations, allowed me to explore the narrative more freely. I can only hope that I succeeded in capturing the weight and feel of “epic time” in Ang Sandali ng mga Mata.

—Alvin Yapan

I began translating Alvin Yapan’s Ang Sandali ng Mga Mata (ADMU Press, 2006), which I would eventually call Time of the Eye, in early 2024, more than a year since I moved to Bangkok, Thailand, to pursue my PhD. By then, I thought I could finally try translating Yapan’s work. I already tried doing so before, even completing two of his short stories and a couple of chapters from his sophomore novel Sambahin ang Katawan (TAPAT, 2011), but for some reason, I hesitated for so long from even attempting to translate Sandali simply because I knew how difficult the task would be. At the time, however, I felt that I’ve had a considerable growth as a translator not only because of my recent translation of Jaya Jacobo’s Arasahas: Poems from the Tropics (PAWA Press and Paloma Press, 2024); but also because I’ve developed a new relationship with the English language, which I had to primarily use, being in another country whose vernacular I could barely speak.

“Mga Alamat sa Bayan ng Sagrada,” translated here as “Legends of Sagrada,” is an early version of Sandali. In Yapan’s words, it is a finger exercise from which the novel eventually emerged. By the time I translated the short story, I had finished drafting more than half of Time. And so, working on “Legends” came quite naturally, as I’ve become mostly familiar with Yapan’s prose, which is often entangled but consistently sings—a quality I always aim to evoke, or at least to provide an analog for, in my translation of his work. In “Legends,” as in most of the translations I do, as much as I tried following the syntax and sentence order in the original, I also deliberately played with them every so often to hopefully produce a certain music in the English translation.

—Christian Benitez

Naniniwala ako noon sa mga alamat, na may katumbas na paliwanag sa pinagmulan ng bawat bagay sa paligid natin. Ngunit nagbago ang lahat ng ito nang minsang mapadaan ako sa Bayan ng Sagrada. Naitanong ko so kanila noon kung saan nanggaling ang pangalan ng bayan. Kuwento nila, noong panahon ng Kastila, ang Sagrada Familia ang ibinigay na pangalan sa kanilang lugar. Ngunit dahil mahabang bigkasin ang Sagrada Familia, kinaltas na lamang ang Familia sa pagdaan ng panahon. Doon daw nanggaling ang kanilang pangalan. Kahit wala naman daw talagang sagrada sa kanilang bayan.

Sa bayang ito ko nakilala si Miguel. Nakita ko siya sa harap ng Kolehiyo ng Lourdes na nasa tabi lamang ng highway, na humihiwalay dito sa kaharap na sementeryo sa puso ng Bayan ng Sagrada. Sumisigaw noon si Miguel, pinangangaralan ang mga taong patuloy lamang sa pagdaan sa harap niya. Pinakinggan ko ang kaniyang pangangaral, palibhasa’y hindi pa manhid ang tenga ko sa mga sigaw niya.

Nakita na raw niya si Sita. Mag-iingat daw sa paglalakad at baka matapakan ang mga kamay at paa ng mga taong wala namang nakakakita maliban sa kaniya. Sari-saring amoy at tunog rin ang nalalanghap at naririnig ni Miguel sa hanging walang sinumang nagtatangkang sumagap dahil sa dalang makapal na usok ng mga nagdaraang bus at dyip. Sari-saring pangitain ang nakikita niya sa kolehiyong punong-puno ng mga nag-aaral na estudyante.

Ginawan na lamang ng alamat ng mga taga-Sagrada ang kabaliwan ni Miguel gayong hindi naman nila ito maintindihan. Papatapos na raw sa kolehiyo si Miguel bilang inhinyero nang mabaliw. Hindi natanggap ng mga magulang nito ang kinasapitan ng kaisa-isang anak. Mayaman silang pamilya. May-kaya lamang ang nakapagpapaaral ng anak sa Kolehiyo ng Lourdes na pagmamay-ari ng mga madre. Sa pagkabaliw ni Miguel, tiyak mamamatay ang pangalan ng kanilang angkan. Hindi naharap ng mga magulang ni Miguel ang takot na nananalaytay sa dugo nila ang sumpa ng kabaliwan. Iniwan nila ang Bayan ng Sagrada. Iniwan nila si Miguel na sumisigaw sa harap ng Kolehiyo ng Lourdes. Ipinamana na lamang sa Bayan ng Sagrada ang mansiong ngayo’y kinatatakutan at pinamumugaran ng mga multo. Nakulong sa panahon ng Kastila ang mansiong ito: mga kapis na bintana, de-balustreng balkonahe, mga narrang pinto at hagdang tumutuloy sa ikalawang palapag. Malawak ang bakuran na ngayo’y punong-puno na ng mga talahib na walang tigil sa pagyuko’t pagsamba sa matandang mansion.

Nang kupkupin ni Juanito ang baliw na binata sa bahay-bahayan niya sa likod ng kolehiyo, lalong napagtibay ng mga taga-Sagrada ang paghihinalang ang diyanitor ang may kasalanan sa lahat ng nangyari kay Miguel. Si Juanito ang sumagip kay Miguel sa unang araw ng pagkabaliw niya. Tumakbo si Miguel sa gitna ng highway; balak harangin ang rumaragasang pampasaherong bus na papauwi galing sa Maynila. Paliwanag ni Miguel, pagkatapos silang sagipin ni Juanito, na masasagasaan daw kasi ng bus ang mag-anak na nakalupaypay sa gitna ng highway. Humagulgol si Miguel at pinagalitan si Juanito dahil hinayaan nitong magkalasog-lasog ang mga katawan ng mag-anak.

Magmula noon, ang bahay-bahayan na ni Juanito ang naging mansion ni Miguel. Hindi naman tumutol ang mga madre. Ipinagpaalam lamang ni Juanito sa mga madre ang paninirahan doon ni Miguel. Idinahilan nito ang kaniyang katandaan. Nangangailangan na raw siya ng katulong bilang tagalinis ng kolehiyo sa umaga, tagabantay sa gabi, at bilang katiwala ng mga madreng nakatira sa hiwalay at tagong lugar sa Bayan ng Sagrada ang makapanalangin daw sila nang mapayapa. Hindi naman daw nanggugulo si Miguel. Puwede namang pabayaan at huwag na lamang pansinin ang mga pangangaral nitong hindi naman kasintindi ng sermon ng kura paroko ng Bayan ng Sagrada.

Hindi nagtagal, nakita na ng buong bayan na tumutulong na si Miguel sa mga gawain ni Juanito. Iniipon niya ang mga tuyong dahon sa bakuran ng kolehiyo, saka sinisigaan. Pinakikintab niya ang pasilyo ng mga gusali ng kolehiyo. Kapag uwian na, katulong naman siya ni Juanito sa pagbubura ng mga pisara at pag-aayos ng mga silya. Higit sa lahat ng gawaing ito’y ang paglilinis niya ng grotto ng kolehiyo. May dumadaloy itong tubig mula sa gripong nakatago sa likod ng santang nakakubli sa loob ng sementong kuweba. Dumadaan ang tubig sa paanan ng kuweba kung saan nakaluhod ang isa pang Santa, saka tumutuloy sa artipisyal na palaisdaan na nilalanguyan ng mga isdang napakagagara ng palikpik at napakatitingkad ng kulay ngunit hindi naman napakikinabangan bilang pagkain. Araw-araw na dinadalaw ni Miguel ang grotto upang alisin ang mga dahong nalalaglag sa tubig. Tinitiyak niyang maayos at tuloy-tuloy ang pagdaloy ng tubig mula sa likod ng Santa patungo sa mga isda. Kapag natapos na ang lahat ng gawain ni Miguel sa kolehiyo, nakikita siyang palakad-lakad sa tabi ng highway na parang hindi makapagpasya kung tatawid papunta sa sementeryo o papasok sa kolehiyo. Pinangangaralan niya ang nagdaraang mga mag-aaral at dumadaan na mag-iingat sa kanilang paglalakad.

Magkahalong buntong-hininga at awa ang reaksiyon ng Bayan ng Sagrada sa pagkabaliw ni Miguel. Kahit papaano raw, natigil na rin ang patayan sa kanilang Bayan ng Sagrada. Si Miguel ang huling biktima ni Juanito sa paghihiganti nito sa bayan. Labis daw na trahedya ang dumapong parang sakit sa buhay ng matandang diyanitor. Kapwa namatay ang asawa’t kaisa-isang anak nito. Ni hindi raw alam ng diyanitor kung saan nakalibing ang kaniyang asawa dahil tuwing Todos los Santos, palakad-lakad ito sa masisikip na pasilyo ng sementeryong punong-puno ng mga taong nag-iinuman at naghahalakhakan, naghahanap ng lugar na mapagtitirikan ng kandila para sa kaniyang asawa sa ibabaw ng mga hinawing damo at itinambak na lantang mga bulaklak. Pati raw ang lupang pagmamay-ari nito ay kinamkam ng mga madre upang mapagtayuan ng Kolehiyo ng Lourdes. Tinira na lamang sa kaniya ang kakapiranggot na lupang kinatitirikan ngayon ng kaniyang bahay-bahayan at ginawa siyang diyanitor ng kolehiyo.

Mangkukulam daw kasi dati ang matandang diyanitor. Ipinambayad niya ang kaniyang asawa at anak sa kasalanan ng paggamit ng itim na kapangyarihan. Ngunit sa halip na magsisi, naghiganti siya sa mga taga-Sagrada. Kumukuha raw ang diyanitor ng isang bata, binatilyo man o dalagita, taon-taon mula sa mga mag-aaral ng Kolehiyo ng Lourdes upang magsilbing kapalit ng asawa’t anak bilang kasama sa bahay-bahayan niya. Pinapatay niya ang mga bata at itinatapon ang bangkay sa sementeryo ng bayan. Taunan ang pagpatay dahil isang taon lamang maaaring manatili ang kaluluwa ng tao sa lupa. Sa loob ng isang taon, ikinukulong ng diyanitor ang kaluluwa ng kaawa-awang bata sa bahay-bahayan niya. Kapag hindi na niya mapigilan ang pag-akyat ng kaluluwa sa langit, mag-iisa na namang muli ang matandang diyanitor at muli na namang mawawala ang isang mag-aaral sa Kolehiyo ng Lourdes.

Hindi raw talaga ang nahuli at umaming lalaki ang salarin. Pinaikot lamang daw ng diyanitor ang isip ng lalaki upang umamin at linisin ang pangalan niya sa mga naganap na patayan. Nang hindi na muling nagduda ang mga tao, nagpasya ang matandang diyanitor na kumuha na ng permanenteng mag-aalaga sa kaniya sa pagtanda. Si Miguel nga ang napili. Pinaikot daw ng matandang diyanitor ang isip ng binata hanggang mabaliw. Nagsimula raw ang lahat nang masaksihan ng mga taga-Sagrada kung paano ipinaglaban ni Miguel sa harap ng mga madre ang karapatan ni Juanito bilang orihinal na nagmamay-ari ng lupang kinatatayuan ng Kolehiyo ng Lourdes.

Ngunit usap-usapan lamang ito. Kahit ganito ang mga bintang nila kay Juanito, hindi nila ito mapalayas sa Kolehiyo ng Lourdes. Unang-una sa lahat, wala silang pinanghahawakang katibayan kundi mga sabi-sabi. Ayaw naman nilang usisain ang matandang diyanitor dahil baka matulad pa sila kay Miguel na nabaliw. Sapat na sa kanila, sa Bayan ng Sagrada, ang alamat ukol sa kabaliwan ni Miguel na sila rin mismo ang may gawa.

Ngunit hindi ako naniwala sa kanilang alamat. Hinanap ko ang matandang Juanito upang tanungin tungkol sa tunay na alamat ng kabaliwan ni Miguel. Natagpuan ko siya sa kaniyang paglilinis. Ngunit bago pa man ako makapagtanong, nakita ko na, narinig ko na, ang sagot ng mga mata niyang nangusap na punong-puno ng kalungkutan.

“Ninais ni Miguel ang nangyari sa kaniya.”

“Tiyong Nito, gusto ko pong makita si Sita.”

“Bakit ka sa’kin lumalapit?”

“May alam daw po kayo sa mahika.”

“Sino’ng may sabi sa’yo niyan?”

“Sila.”

“Sinong sila?”

“Kung sino-sino.”

“Hindi pa ba sapat ang mga kuwento ko sa’yo at gusto mo pa siyang makita?”

“Gusto ko lang po siyang makausap.”

Nasa grotto siya noon nang lapitan ni Miguel. Tama sila, paliwanag noon ni Juanito sa binata. Kaya niyang buksan ang mga mata ni Miguel sa mundo ng mga kaluluwa. Ngunit hindi siya makapipili ng nais niyang makita. Ang kabuoan ng mundong ginagalawan ng mga kaluluwa ang masisilayan ng kaniyang mga mata at kadalasang nababaliw ang sinumang makakita dito. Kaya pili lamang ang nakakakita sa mga kaluluwa. Ito ang ikinakatakot ni Juanito.

“Baka hindi mo makayanan ang makikita mo.”

“Hindi ako natatakot!”

“Nagkamali ako. Muli na naman akong nagkamali.”

“Ano ang ibig mong sabihin?”

“Pinatay ko na sana sa alaala ko ang alamat ng aking mag-ina.”

Ang alamat ni Sita, ang white lady na sinasabing umaali-aligid sa mga pasilyo ng Kolehiyo ng Lourdes, ang ina ng alamat ng kabaliwan ni Miguel. Sabi ng ibang nakakita, nakasuot daw ng baro’t saya ang white lady. Hindi ito kapani-paniwala, sabi naman ng iba. Sa pagkakaalam nila, nightgown ang suot ng white lady na para bang nagkaroon lamang ng mga ligaw na kaluluwa sa Pilipinas nang iniangkat na sa bansa ang nightgown.

Kaya minsan, inagahan ni Miguel ang pagpasok sa klase upang hanapin si Juanito at tanungin ukol sa mga kuwentong ito. Kung totoo nga ba o hindi, si Juanito ang makaaalam dahil nakatira ito sa kolehiyo nang beinte-kuwatro oras. Imposibleng hindi pa niya nasusumpungan ang white lady kung mayroon man. Hindi nga nagkamali si Miguel. Nakita na ni Juanito ang white lady. Kung minsan sa kaniyang pagwawalis sa bakuran dadaanan na lamang siya nito galing sa likuran. Kung minsan kapag nagtatapon siya ng basura sa likod ng kolehiyo, nagpapakita sa kaniya ang white lady sa pag-alimbukay ng alikabok ng chalk sa hangin. Akala niya minsan namamalik-mata lamang siya dahil kasimputi ng alikabok ang white lady. Ngunit sa paghupa ng alikabok, nananatiling nakapagkit sa hangin ang anyo nito.

Hindi pa nakikita ni Juanito ang mukha ng white lady ngunit alam niyang ito ang kaisa-isang anak niyang namatay na dalaga, si Sita. Nalaman ito ni Juanito sa pamamagitan ng mga kuwento sa kaniya ng mga sinasabing pinagpala ng mga buhay na nunal sa noo o sa likod, mga kilay na nagsasalubong, at mga balahibong parang uli-uli sa likod na nagbibigay sa kanila ng kapangyarihan upang masulyapan man lamang ang mundo ng mga kaluluwa. May sinasambit daw na pangalan ang white lady. Nang sabihin sa kaniyang Fred ang pangalan, nawala ang pandududa niyang ito nga ang kaniyang anak na si Sita. Si Fred ang kasintahan nito. Patay na rin si Fred ngunit hindi pa siguro nagkakatagpo ang mga kaluluwa nila, paliwanag ni Juanito sa sarili kung bakit nagpapakita pa rin sa kaniya si Sita.

Kinausap noon ni Juanito ang naligaw na kaluluwa ng anak. Wala siyang hinto sa pagkukuwento at pakikipag-usap habang nagtatrabaho, nagbabaka-sakaling nasa paligid lamang si Sita at naririnig siya. Minsan sa kaniyang pakikipag-usap, bigla na lamang may dumapong itim na paruparo sa mga labi niya. Nagbibigay noon ng payo si Juanito na patahimikin na sana ni Sita ang sarili nitong kaluluwa. Patay na si Fred. Wala na itong dapat hintayin sa lupa. Napatay si Fred ng mga militar. Magmula noon hindi na muling sinambit ni Juanito ang pagkamatay ni Fred. Paminsan-minsan, binibisita pa rin siya ng itim na paruparo. Bigla na lamang itong dumadapo sa kaniyang balikat at nananatili roon hanggang matapos niya ang kaniyang paglilinis. Minsan naman nakararamdam na lamang siya ng malamig at banayad na hangin na parang pinapaypayan siya. Ang inaalagaan niyang mga rosas sa grotto ay nagmimistulang higanteng pakpak ng paruparo.

“Pa’no siya namatay, Tiyong Nito?”

“Panahon noon ng mga binti at paa.”

Nabubuhay ang lahat ng tao noon nang may malaking pagkakautang sa mga binti at paa nila. Sa mga tinutugis ng kampon ni Marcos sa ilalim ng batas militar, napakahalaga ng mga binti at paa sa pagtakbo at paglukso sa pagligtas sa kanilang buhay. Kailangang matibay ang kalamnan ng kanilang binti nang maging handa sa malayuan at mabilisang pagtakbo sa mga pasikot-sikot na eskinita ng kalunsuran o sa luntiang kasukalan ng kagubatan. Kailangang may mata ang talampakan ng mga paa nila upang matandaan ang bawat uka at bato sa daan at nang malaman kung kailan at kung saan tatalon o iiwas nang hindi madapa at mahuli ng mga humahabol. Sa mga pilit namang mamuhay sa loob ng batas militar, kailangang matatag ang mga binti at paa nang hindi tumakbo sa takot kapag napapalapit ang mga kampon ni Marcos. Katulad ng pag-iwas sa kagat ng aso. Kapag nilapitan daw ng aso, hindi ipinapayong umiwas at tumakbo dahil tiyak na hahabuli’t kakagatin. Kailangang malakas ang loob ng binti at paa sa pananatili sa kinatatayuan nang masiguro ng aso sa paglapit na walang inililihim ang kaniyang pinagbabantaang kagatin.

Natamaan noon si Fred sa binti sa isang engkuwentro ng NPA at militar. Kasapi si Fred ng New People’s Army. Bumisita ang pangkat niya noon sa kabayanan upang mamili ng pagkain at iba pang pangangailangan ng grupo sa pagtatago. Natiktikan sila ng isang informer. Humantong ang habulan sa sementeryong kaharap ng Kolehiyo ng Lourdes. Nagkataong panahon noon ng paglalakad ni Sita sa loob ng sementeryo sa paghahanap sa kaluluwa ng kaniyang ina. Hindi alam ni Juanito noon kung matutuwa siya o malulungkot para kay Sita. Natuwa siya dahil nakatagpo na rin ang kaniyang anak ng mamahalin. Lalampas na sa kalendaryo ang gulang nito dahil sa pagkukulong at paggagala sa sementeryo.

Itinago ni Sita ang pangkat nina Fred sa loob ng kolehiyo. Inalis ni Sita ang balang bumaon sa binti ni Fred. Marunong na noon si Sita sa mga pagtuturo ni Juanito na kung minsa’y albularyo rin. Iniwan si Fred ng kaniyang mga kasamahan sa pangangalaga ni Sita. Mapapabagal lamang ang pagtakbo ng iba pang mga binti at paa ng pangkat dahil lamang sa isang nasugatan. Inalagaan naman ni Sita si Fred. Hinihilot niya ang mga hapo nitong paa at tinapalan ng mga dahon at ugat ang sugatang binti hanggang sa humilom. Hindi nagtagal at nabighani si Fred ng kayumangging binti ni Sita. Nang dumating ang panahon ng pamamaalam ni Fred, nangako itong babalik at bibisita paminsan-minsan. Natupad nga ang pangakong ito at nauwi sa magkatabing paglalakad ng kanilang mga binti at paa sa sementeryo kung saan sila parating nagtatagpo. Dito nalungkot si Juanito para sa anak niya. Kailangan pang maganap ang pag-ibig nito sa pagtatago sa sementeryo ng Bayan ng Sagrada.

Isang gabi, nagising na lamang sina Juanito at Sita sa daan-daang binti’t paang naghahabulan sa bakuran at pasilyo ng Kolehiyo ng Lourdes. Agad tumakbo sa labas si Sita. Natagpuan ng kaniyang mga binti at paa si Fred na sumunod naman kaagad sa dalaga, kasunod ang mga kasamahan nitong NPA. Ituturo sa kanila ni Sita ang daan sa likod ng kolehiyo kung saan sila maaaring tumakas patungong kabundukan. Subalit walang laban ang mga paa nilang naka-tsinelas lamang o kaya naka-tennis sa humahabol na nakabotang mga paa na parang mga pisong pumapatag sa anumang nakaharang at nakahambalang sa daan nito, bakod man o namumulaklak na halaman. Naabutan sila ng mga militar. Nahinto ang pagaspas ng mga binti at paa sa pasilyo ng Kolehiyo ng Lourdes. Sumambulat ang mga bala sa baril ng mga militar. Hindi ngayon sa binti humantong ang mga bala kung hindi sa dibdib ni Sita. Muling tinugis ng nakabotang mga paa ang binti at paa ng kasintahan ng dalaga. Hindi naabutan si Fred at nakaligtas sa kamatayang bumawi sa buhay ni Sita.

Dinala ni Juanito si Miguel sa grotto.

“Pinatayo ko ang grottong ito sa alaala ni Sita. Dito sa lugar na ito namatay ang aking si Sita.”

Bumuo si Miguel ng isang samahang magpoprotesta sa mga palakad ng mga madre sa Kolehiyo ng Lourdes. Ang pangkat na ito ni Miguel ang nagpasimuno sa mga sit-down strike bilang protesta sa mga pagdadagdag ng tuition fee dahil accredited ang Kolehiyo ng Lourdes. Itinampok ng grupong ito ang kalagayan ni Juanito bilang diyanitor ng kolehiyo na hindi nakatatanggap ng sapat na sahod gayong napakataas na ng itinataas ng matrikula taon-taon.

“Para saan ang lahat ng ’yong ginagawa, Miguel?”

“Para sa’yo.”

“Kung gayon, itigil n’yo na ang lahat ng pakikipaglaban sa mga madre.”

“Bakit? Ayaw mo bang mabawi ang lupa mo sa kanila?”

“Ibinigay ko sa mga madre ang lupa. Kusa kong ibinigay.”

“Bakit?”

“Aanhin ko naman ‘to. Malawak ang lupang ito. Patay na ang asawa ko. Pati ang anak ko.”

“Nang walang bayad?”

“Ang mga madre ang nagbigay sa akin ng grotto.”

Ikinuwento ni Juanito kay Miguel kung paano isang araw nagmamadaling umuwi si Sita. Nakita na raw nito ang kaluluwa ng kaniyang ina sa sementeryo. Tinanong siya ni Juanito kung ano ang hitsura nito. Hindi nakuhang mailarawan ni Sita ang ina niya hanggang sa makita ang estampa ng patron ng kolehiyo. Kamukha raw ng Birhen ng Lourdes ang kaniyang ina.

“Ayaw kong matulad ka kay Sita, Miguel. Namatay siya sa pagsamba sa alaala ng kaniyang ina.”

“Ano ang pangalan niya?”

“Gloria.”

Isang araw ng taong 1944, nadatnan ni Juanito ang kaniyang bahay na napaliligiran ng napakaraming mapag-usisang mata ng mga sundalong Hapon. Galing pa lamang noon si Juanito sa kaniyang sakahan. Sa gitna ng mga mata ng mga dayuhang sundalo, may naligaw na matang nakasilip lamang sa dalawang butas ng bayong. Gumalaw ang matang ito at napako sa mga mata ni Gloria na nakatayo noon sa pintuan ng bahay nila ni Juanito. Magkahalong takot at galit ang nasa mga mata niya. Itinuro siya ng Makapili. Nagmura si Gloria. Tinawag na duwag ang matang nagtatago sa loob ng bayong. Lalong sumingkit ang mga matang nakapalibot sa kubo. Nakita nila si Juanito.

Nangyari ang ikinakatakot ko noon. Sabi ko sa ’king asawa huwag na huwag siyang magpapatuloy ng gerilya sa aming bahay. Nang araw na iyon, hindi nakinig sa akin si Gloria. May natagpuang walong gerilyang lalaki na nagtatago sa bahay namin.

Iginapos silang lahat sa labas ng bahay ni Juanito at pinalinya. Tinutukan sila ng bayoneta ng mga Hapon sa likod nang hindi mapikit ang mga mata nila habang ginagahasa si Gloria sa harap nila. Parang naupos na kandila noon ang buhay sa mata ni Gloria habang nandidilat ang mga mata ng mga sundalong Hapon. Parang ninanakaw ang buhay ni Gloria ng mga mata ng Hapon na lalong lumaki sa bawat pagbayo nila sa asawa ni Juanito.

Pagkatapos, pinaghukay silang mga lalaki sa lugar na ngayo’y katatagpuan na ng sementeryo. Pinaghukay sila ng paglilibingan sa kanila kinaumagahan. Nang gabing iyon hindi makapikit ang mga mata ni Juanito. Sa kauna-unahang pagkakataon, hindi nagbadya ng pag-asa ang bukang-liwayway kundi ng kanilang kamatayan. Pupugutan sila ng ulo sa pagsikat ng unang silahis ng araw sa abot-tanaw.

Nakapalibot sila noon sa siga nang makita agad sila sa liwanag ng mga tagabantay kung magtangka man silang tumakas. Nakagapos ang mga kamay nila. Sa liwanag ng siga, nasaksihan noon ng mga mata ni Juanito kung bakit siya sinuway ni Gloria sa pagpapatuloy ng mga gerilya sa kanilang bahay. Nakahilig ang luhaang mata ni Gloria sa dibdib ng dati niyang karibal, si Pedring. Akala niya’y nakalimutan na ng kaniyang asawa si Pedring na natalo niya dahil wala itong lupang pagmamay-ari na maaaring pagsakahan at ipagmayabang sa mga magulang ni Gloria. Nang gabing iyon, nakita niya kung paano nagkakapareho ang mga mata nina Gloria at Pedring sa pagdadalamhati.

Ang panibughong naramdaman ni Juanito ang pumawi sa sakit nang ilapit niya ang kaniyang kamay sa apoy upang makalag ang taling gumagapos sa kaniya. Hindi si Gloria ang una niyang pinakawalan kundi ang isa sa mga kasamahan ni Pedring. Inutusan niya itong ipagpatuloy ang pagkalag sa gapos ng iba at kukunin lamang niya si Sita na noo’y isang taong gulang pa lamang na sanggol na nakaligtaan sa loob ng kubo. Hindi na nakuha pa ni Juanito ang bumalik upang tulungan ang iba dahil nagising na ang mga mata ng sundalong Hapon. Tumakbo agad siya papalayo dala-dala si Sita na umiyak nang umiyak kung kaya nasundan sila ng mga Hapon sa dilim.

Nang matambad siya sa kahabaan ng isang tulay, agad siyang tumalon. Hindi na niya matatawid ang tulay dahil papalapit na ang mga Hapon. Napakataas ng tulay, nagpasalamat na lamang siya sa kaniyang mga mata dahil ipinakita nito sa kaniya na kaya niyang talunin ang tulay. Natalon nga niya ang tulay subalit nasundan pa rin siya ng mga Hapon sa mga pag-iyak ni Sita hanggang sa maharap si Juanito sa nakalululang kapatagan ng isang sakahan. Nakita ni Juanito ang kamatayan niya sa luntian at hitik na hitik na kabukiran. Hindi niya alam kung paano siya hindi makikita ng mga Hapon sa kapatagang ito ngunit ipinagpatuloy pa rin niya ang pagtakbo. Nadapa na lamang siya at nahulog sa putikang paliguan ng mga kalabaw.

Ang putikan ang nagligtas kina Juanito at Sita. Kinulapulan sila ng itim na putik ng kadilimang hindi matarok ng mga mata ng mga sundalong Hapon. Napilitang suntukin ni Juanito ang anak nang matigil ito sa pag-iyak at nang hindi sila matunton ng mga Hapon. Nang mag-umaga na, tumakas si Juanito sa kagubatan dala si Sita upang sumapi sa mga gerilya. Wala na siyang ibang mapupuntahan dahil tiyak niyang mamumukhaan siya ng mga Hapon.

Ipinamalita niya ang nangyari kay Gloria at sa pangkat ni Pedring. At sa kuwentong iyon ng pagtataksil sa kaniya ng asawa, naisilang ang kabayanihan ni Gloria.

“’Yon ang hindi naintindihan ni Sita, Miguel. Walang bayani sa bayan natin.”

“Ayaw kong mapunta sa wala ang pagkamatay ni Sita.”

“Hindi pa ba sapat ang mga kuwento ko sa’yo at gusto mo pa siyang makita?”

“Gusto ko lang po siyang makausap.”

Nasa grotto silo noon nag-uusap ni Miguel. Hindi pumayag si Juanito.

Magmula noon, tuwing dadalaw si Juanito sa grotto, makikita niyang nakatanghod doon si Miguel, pinagmamasdan ang mga isda, ang santong nakaluhod, at ang santong nakatago sa sementong kuweba. Unti-unti nang nagiging bahagi ng grotto ang binata. Nagsisi noon si Juanito, isang pagsisising bumalot ng kalungkutan sa mga mata niya hanggang ngayon. Dumarami na nang dumarami ang nababato-balani ng dalawang santang nanigas na sa kanilang pagtititigan. Kinalimutan na sana niya ang alaala ng kaniyang mag-ina. Hindi na sana nadamay ang binata. Maaari pang masagip ang binata, naisip niya isang araw. Maaari pa siyang umasa na makakayanan ni Miguel ang anumang lihim na ikinukubli ng mga kaluluwa sa mundo nila. Pumayag na tumulong si Juanito na makita ni Miguel ang mundo ng kaluluwa.

Binuksan ni Juanito ang mga mata ni Miguel at gayon nga ang nangyari. Nakita ni Miguel ang buong daigdig na kinabibilangan ni Sita. Nakita niya ang panahon ng mga binti’t paang nangyayaring kasabay ng panahon ng mga mata. Humahagunot sa hangin ang mga punlong tumutugis sa mga binti. Pumapailanlang sa bughaw na kalawakan ang mga halakhak ng gumagahasa kay Gloria. Inaalala ng pagaspas ng mga dahon ang tunog ng mga paa sa pasilyo ng Kolehiyo ng Lourdes. Umaalingawngaw ang mga pag-iyak ni Sita bago siya suntukin ng kaniyang ama. Tinatawag niya ang mga Hapon na kitilin na ang kaniyang buhay hangga’t maaga pa. Nasaksihan ni Miguel ang daloy ng kabit-kabit na alamat. Mga pusong pilit pinaghiwalay at pinagniig ng mga lupang kumupkop sa mga ulong nalagas sa puno ng kanilang mga katawan sa pagdating ng bukang-liwayway na nagbibigay daan sa mga araw na inuubos sa paghahanap ng alaala ng dinakilang ina sa loob ng sementeryong kaharap ng kolehiyong hindi maiwan-iwan ng isang kaluluwang hindi makausap ng isang binatang nais makaunawa’t nabaliw dahil pinaglaruan daw ng isang matandang habambuhay na lamang na mamumuhay nang nag-iisa ayon sa mga taga-bayan ng Sagrada. At marami pang kuwentong kasangkot ng iba’t ibang bahagi ng katawan. Kamay na nakatakip sa mga duguang tenga. Likod na hindi makaligtas sa mga hagupit. Mga bibig na nagpapakawala ng mga ungol at balahaw. Mga balikat na hindi makayanan ang mga pinapasan. Ipinuputang mga ari. Mga leeg na sinasakal ng mga lubid. Mga ilong na manhid na sa amoy ng nabubulok nang mga bangkay. Nakita ni Miguel ang baha-bahaging katawan ng milyon-milyong taong nakaratay hanggang abot-tanaw kung saan nagtatagpo ang langit at lupang kapwa pinapula ng mga ilog ng dugong bumubukal sa mga puso ng di-mabilang na mga bangkay. Nakita niya sa isang iglap kung paano binubuntis ng panahon ang mga alamat na nanganganak ng buntis na ring mga alamat.

Sa harap ng lahat ng ito, naintindihan ni Miguel ang lahat ng pinagmulan ng mga bagay-bagay sa paligid ng Bayan ng Sagrada. Noon nagsimulang lumabas sa bibig niya ang mga salitang wala namang nakaiintindi dahil iba na ang kaniyang ginagalawang daigdig kung saan bago pa man ang pangyayari ay nalilikha na ang alamat.

Mahirap paniwalaan ang mga alamat. Walang dapat sisihin. Hindi ko rin pinagkatiwalaan ang nilikhang alamat ng Bayan ng Sagrada para sa kabaliwan ni Miguel. Kahit pangalan ng kanilang bayan, hindi nila maipaliwanag ang pinagmulan. Natanong ko sa kanila noon kung saan nanggaling ang pangalan ng bayan nila. Wala naman daw talagang sagrado sa kanilang lugar. Wala raw akong matatagpuang alamat ng pangalan ng kanilang bayan. Ang binigkas nila akin ay mga kuwento na lamang.

I used to believe in legends, that there exists a story for each thing around us to explain its origin. But all this changed when once I happened to be in the town of Sagrada and asked the people how the place got its name. They told me then that it was the Spaniards who christened their town Sagrada Familia. But since the name was a bit of a mouthful, the people eventually dropped the Familia. From then on, their town came to be known simply as Sagrada, despite the fact that there was nothing sacred about their town.

It was during this time that I first saw Miguel. He was standing in front of Lourdes College, right beside the highway that separates the school from the cemetery at the heart of Sagrada. He was yelling then, scolding the people who simply passed him by and paid him no mind. I listened to him speak, only because my ears still haven’t turned deaf to his shouting.

He claimed that he has seen Sita. He warned people to walk carefully, lest they step on the hands and feet of people no one else could see. He said that he smelled and heard things in the air, which nobody else would dare to breathe in, filthy as it was with the thick smoke coming from passing buses and jeepneys. He insisted that he has seen visions of the school filled with students.

Because nobody in Sagrada understood Miguel, they eventually came up with a story about him instead. Word began to spread that he was about to graduate and become an engineer when he suddenly went mad. His parents couldn’t believe what happened to their only son. Their family used to be rich; only those with money would send their children to that school run by nuns. As Miguel fell into madness, it was only a matter of time before their family would also fall from grace. His parents dreaded the thought that the curse of madness truly ran in their blood. So they fled the town of Sagrada, leaving their son behind yelling in front of Lourdes College. They abandoned their mansion, feared now by the people of Sagrada for all the ghosts that have since dwelt in it. The mansion appeared stuck in the Spanish colonial period: capiz windows, balustraded balconies, narra doors, and a staircase leading to the second floor. Its wide yard was teeming with wild grass that relentlessly bowed and praised the old house.

When Juanito took the mad young man into his small hut behind the school, people grew wary of the janitor, suspecting him to be the mastermind of everything that had happened to Miguel. It was Juanito who saved Miguel on the day he went mad. Miguel ran to the middle of the highway to stop a speeding bus coming all the way from Manila. Miguel swore that the bus was about to run over a family sprawled on the ground. Miguel broke down, blaming Juanito for letting their bodies be mangled by the bus.

Since then, Juanito’s hut became Miguel’s home. The nuns never complained. Juanito asked them if Miguel could stay. He explained that he was getting old. He needed someone who could help him clean the school in the morning, watch over it at night, and be an all-around caretaker to the nuns, who all lived in a separate and hidden place in the town of Sagrada, so they could say their prayer in peace. Miguel wouldn’t be a bother, Juanito promised. They could just let him be and ignore his grumblings, which never got as loud as the sermons of the parish priest of Sagrada anyway.

Soon enough, the entire town had seen Miguel helping Juanito in his daily chores. He would gather the dried leaves in the schoolyard and light them on fire. He would wax the floor of the hallways in the buildings. After classes, he would help Juanito erase the writings on the board and set the chairs back in order. On top of all this, Miguel would also clean the school grotto. The concrete cave had water flowing through it coming from the faucet hidden behind the praying saint. The water flowed down to the foot of the cave, where another saint was kneeling, then gathered in an artificial pool where fish with gorgeous fins and vibrant colors, but ultimately useless as they were inedible, swam around. Miguel would visit the grotto each day to take out the leaves that fell onto the water. He would make sure that the water flowed smoothly from the back of the saint down to the fish. Once he finished his work in the college, Miguel would be seen standing by the highway, as if he couldn’t make up his mind whether to cross to the cemetery or walk back to the school. He would warn the passing students and pedestrians to be careful on their way.

The people of Sagrada pitied and sighed for Miguel and his descent to madness. But at least, they thought, the killings in their town had finally ended. Miguel was Juanito’s last victim in his revenge on their town. A tragic misfortune had befallen the old janitor’s life like a plague. Both his wife and their only child whom she was still carrying died. But the janitor seemed to not even know where they were buried, because every All Souls’ Day, he would be seen wandering through the narrow paths of the cemetery filled with people drinking and laughing, searching for a place amid the weed and dried flowers he set aside where he could light a candle for his wife. Even the land he once owned was taken away by the nuns to build Lourdes College, leaving him with the meagre piece of land where his little hut now stood. To add salt to the wound, they even hired him to be the janitor of the school.

They believed that the old janitor used to be a witch doctor, and that he had to pay for using black magic with the lives of his wife and child. But instead of repenting, he took revenge on the people of Sagrada. They said that each year, the janitor would take the life of a student from Lourdes College, either a young man or a woman, to replace his wife and child, and to keep him company in his little hut. He would kill them and dump their body in the town cemetery. He had to kill somebody every year, because a soul can only stay here on earth for so long. During this time, the janitor would keep the soul of the poor student captive in his hut. And once he could no longer hold back its ascent to heaven, the old janitor would be left alone once again, and so prompting another student from Lourdes College to go missing.

The people claimed that the man who was caught and has confessed to the murders was not the true culprit. They believed that the janitor somehow tinkered with the man’s head to admit to the crime, clearing Juanito’s name from all the killings. So to finally dispel their fears, the old janitor had to take in someone who would take care of him for good. Someone who happened to be Miguel. They said that the old janitor played with the young man’s head until he finally went mad. Everything began when the entire town of Sagrada witnessed how Miguel stood up to the nuns for Juanito’s rights as the rightful owner of the land where Lourdes College stood.

But these were all just rumors. Despite all these stories about Juanito, the people wouldn’t be able to banish him from Lourdes College. After all, they didn’t have anything but stories. Neither did they want to speak to the old janitor, fearing that they might go mad just like Miguel. It was enough for the entire town of Sagrada to speak of the legend of Miguel’s madness, which they themselves have created.

But I never believed these legends. I looked for old Juanito to ask him the true story behind Miguel’s madness. I found him sweeping the schoolyard. But before I could even ask him anything, I already saw, I already heard, the answer in his eyes filled with sorrow.

“Miguel asked for whatever happened to him.”

“Tiyong Nito, I want to see Sita.”

“Why are you telling me this?”

“Because they say you know something about magic.”

“Who told you that?”

“They did.”

“‘They’?”

“Everyone. The people.”

“Haven’t I told you enough stories? Do you still really want to see her?”

“I just want to talk to her.”

He was at the grotto when Miguel approached him. They were right, Juanito admitted to the young man. There were only a handful of them who could see spirits. He could also open Miguel’s eyes to the world of spirits. But he wouldn’t be able to choose which things he’d then see. His eyes would see the entire world of spirits, and most who did ended up going mad. This was what Juanito feared.

“You might not be able to stand what you see.”

“Well, I’m not afraid.”

“I once made that mistake. I don’t want to make the same mistake again.”

“What do you mean?”

“I wish I just forgot about the legend of my wife and our child.”

The legend of Sita, the white lady said to haunt the hallways of Lourdes College, was the story that gave birth to the legend of Miguel’s madness. Those who claimed to have seen her said that she wore a traditional baro’t saya. But that’s just impossible, others disagreed. In their mind, white ladies have always worn nightgowns—as if lost souls appeared in the country only after nightgowns began being imported here.

So one day, Miguel went to Lourdes College early to look for Juanito and ask him about the stories he had heard. If there was anyone who would know whether they were true, it was Juanito, who stayed in the school twenty-four hours a day. If there really was a white lady, it was impossible that the janitor had never seen her. And Miguel was right: Juanito had indeed seen the white lady. Sometimes, as he swept the schoolyard, she would pass right behind him. Or as he took out the trash at the back of the school grounds, the white lady would show herself in the whirling of chalkdust in the air. He would think then that he was only imagining things, because the white lady was truly as white as the dust. But as the dust settled, her form would remain suspended in the air.

Juanito still hadn’t seen the face of the white lady, but he already knew it was his dead daughter Sita. Juanito realized this from the stories he heard from those blessed with growing moles on their foreheads or their napes, those with unibrows or cowlicks at the back of their heads, which were all believed to open their eyes to the world of spirits. They all claimed that the white lady kept uttering a name. And when they all told him it was Fred, Juanito was certain that the white lady was his daughter Sita. Fred was her lover, and he, too, has been long dead. But perhaps, they still haven’t found each other as lost souls, Juanito told himself, explaining why Sita still appeared to him every so often.

Juanito began to talk then to his daughter’s soul. He constantly spoke on his own, telling stories as he worked, hoping that Sita was just around, listening. Once, as he chattered on, a black butterfly landed on his lips. Juanito told Sita then to finally let her spirit rest. Fred was already dead. She no longer had to wait for him here on earth. Fred was killed by the military. Since then, Juanito never spoke again about Fred’s death. Sometimes, the black butterfly would still visit him. It would land on his shoulder and stay there until he finished cleaning. Other times he would feel a cold and calm air as if someone were fanning him. The roses in the grotto he took good care of would seem like giant wings of a butterfly.

“How did she die, Tiyong Nito?’’

“It was a time of legs and feet.”

Everyone owed their life then to their legs and feet. To those who were pursued by Marcos’s henchmen under Martial Law, legs and feet were crucial to run and jump to save their lives. The muscles of their legs had to be strong, to be ready for long and fast sprints through the labyrinthine alleyways in the city or the winding thickets in the forest. The soles of their feet had to have eyes to remember each stone and crevice on the way, to know when and where to jump or flee, so they wouldn’t fall and be caught by their pursuers. And those who insisted on living under Martial Law needed their legs and feet to be just as strong, so they wouldn’t turn and run away in fear when Marcos’s henchmen neared. Just like when a dog senses fear. When a dog approaches, it is never good to turn and run away, as it would only end up chasing to bite. So legs and feet needed to have a strong heart to stay still where they stood, so whenever the dog approached, it would be convinced that the one it threatened to bite really had nothing to hide.

Fred was shot in his leg in a crossfire between the NPA and the military. Fred was part of the New People’s Army. At the time, his team was visiting the town to buy food and other necessities for the troop during their hiding. Someone told the military about them. The pursuit ended in the cemetery right across Lourdes College. And just then, Sita happened to be wandering in the cemetery, looking for her mother’s lost soul. Juanito didn’t know then whether to be happy or sad for his daughter. He was happy for she had finally found someone to love. She was already past the ripe age for marriage, having spent most of her time alone wandering the cemetery.

Sita took Fred’s squad to the school. She took out the bullet buried in Fred’s leg. Sita had already learned a lot by then from Juanito, who was also a healer. Fred’s company left him to Sita’s care. The rest of the team’s legs and feet would only be slowed down by the wound. So Sita took care of Fred. She massaged his weary feet and put leaves and roots on his injured leg until it healed. And soon enough, Fred was mesmerized by Sita’s own brown legs. When time finally came for Fred to bid goodbye, he promised to return to visit every now and then. This promise was kept, and it led to their legs and feet walking alongside each other in the cemetery, where they always met. It was then that Juanito began to feel sadness for his daughter. Her first love had to unfold in hiding in the cemetery of the town of Sagrada.

One night, Juanito and Sita woke up to hundreds of legs and feet running across the schoolyard and in the hallways of Lourdes School. Sita immediately ran outside. Her legs and feet found Fred, who followed the young woman at once, followed by his comrades. Sita was going to show them the way behind the school to escape to the mountains. But their feet in slippers and plain rubber shoes couldn’t keep ahead of all the feet in boots chasing them, feet that flattened like steamrollers whatever it was that blocked their way, be it a flower in bloom or a wooden fence. The constabulary eventually caught up with them. The shuffling of legs and feet in the hallway of Lourdes College then ceased. Shells of military bullets scattered everywhere. Bullets which didn’t end up this time in someone’s leg, but in Sita’s chest. The feet in boots began chasing the legs and feet of Sita’s lover. Fred fled and was spared from the death that finally took Sita away.

Juanito brought Miguel to the grotto.

“I had this grotto built in memory of Sita. It’s where my Sita was killed.”

Miguel once organized a group that would protest against the nuns’ management of Lourdes College. Miguel’s group led sit-down protests against the tuition hike after the accreditation of the school. They especially brought up Juanito’s standing as a janitor who never received enough pay despite the yearly increase in tuition.

“Why are you doing all this, Miguel?”

“It’s for you.”

“If that’s the case, then stop protesting against the nuns.”

“Don’t you want to take your land back?”

“I gave it to the nuns. I gave it to them willingly.”

“Why?”

“Because what am I going to do with all of this? It’s a large piece of land! My wife is dead, my daughter is dead—”

“Without any pay?”

“The nuns gave me the grotto.”

Juanito told Miguel how Sita rushed home one afternoon. She said she saw her mother’s spirit in the cemetery. Juanito asked her how she looked. Sita couldn’t describe her mother’s face until she saw the image of the patron saint of the school. She said that her mother looked just like the Lady of Lourdes.

“I don’t want you to be like Sita, Miguel. She died worshipping the memory of her mother.”

“What was her name?”

“Gloria.”

One day, in 1944, Juanito arrived at his hut surrounded by many pairs of scrutinizing eyes of Japanese soldiers. Juanito had just come back from the fields. Among the eyes of the foreign soldiers, there was a pair of round eyes looking through two holes poked on a bayong. The eyes moved and fell upon Gloria’s eyes, who was then standing by the door of their hut. Her eyes bared fear and rage. The Makapili pointed at her. Gloria cursed. She called the pair of eyes behind the bayong a coward. The rest of the eyes narrowed. Then they saw Juanito.

His worst fear came true. He had told his wife to never let a guerilla into their house. But on that day, Gloria didn’t listen. They found eight guerillas hiding in their hut.

They were all tied up, brought outside Juanito’s hut, and lined up. The Japanese pointed their bayonets at their backs so their eyes wouldn’t shut as Gloria was raped right in front of everyone. The life in Gloria’s eyes quickly melted like a burning candle, as the eyes of the Japanese soldiers grew rounder and rounder. It was as if her very life was drained out of her, while the eyes of the Japanese only grew larger each time they thrusted themselves into Juanito’s wife.

The men were then forced to dig where the cemetery could now be found. They were forced to dig where they would be buried the morning after. That night, Juanito’s eyes wouldn’t shut themselves. For the first time, the sunrise promised not hope but death. They were all set to be beheaded at the first light of the day.

They were all sitting by the fire so the soldiers could easily see if someone tried to run away. Their wrists were tied. By the light of the fire, Juanito’s eyes saw why Gloria didn’t heed his word and let the guerillas into their house. Gloria’s tearful eyes rested on the chest of Juanito’s old rival. He thought his wife had long forgotten about Pedring, whom he thought he already beat and banished from Gloria’s life. Pedring never had any piece of land to farm and to boast to Gloria’s parents. But that night, Juanito saw how Gloria’s and Pedring’s eyes, in grief, became one and the same.

The bitter jealousy in Juanito numbed the pain when he moved his hands toward the flame, burning the rope around his wrists. It wasn’t Gloria whom he first set free but one of Pedring’s comrades. He asked him to untie the rest of them while he went back to the hut for Sita, only over a year old then. But soon after, Juanito could no longer return to help the others, as the eyes of the Japanese soldiers had already opened. So Juanito ran away, carrying Sita, who relentlessly cried, helping the Japanese to track them in the dark.

When he finally arrived on a bridge, Juanito jumped at once. He couldn’t cross the bridge as the Japanese were already close. The bridge was rather high, so he thanked his eyes for seeing he could jump off it. But despite doing so, the Japanese still found him through Sita’s cries, until Juanito finally came to a dizzying expanse of a field. In the green and flourishing ground, Juanito saw his death. He didn’t know where he could hide from the Japanese in this vast plain, but he still kept running. Until he tripped and fell into a puddle of mud where carabaos bathed.

It was this muck that saved Juanito and Sita. They were covered by the black mud with blackness that the eyes chasing them couldn’t see. Juanito was forced to hit his daughter so she would stop crying and the Japanese soldiers would finally lose them. When dawn finally broke, Juanito went to the forest with Sita to join the guerillas. He had nowhere else to go, for he knew that the Japanese would remember him. He told the guerillas what happened to Gloria and Pedring’s group. And from the story of his wife betraying him, the legend of Gloria’s bravery was then born.

“That’s what Sita couldn’t understand, Miguel. There’s no hero in our town.”

“I don’t want Sita’s death to be for nothing.”

“Haven’t I told you enough stories? Do you still really want to see her?”

“I just want to talk to her.”

They were talking then by the grotto. Juanito said no.

Since then, each time Juanito would visit the grotto, he’d see Miguel with his head bowed, looking at the fish and the saint kneeling, then turning to the praying saint in the concrete cave. The young man was slowly becoming a part of the grotto himself. Juanito began to feel a pang of regret, a regret that shrouded his eyes with sorrow until now. More and more Miguel grew fascinated with the two saints petrified in each other’s gaze. Juanito should have forgotten the memory of his wife and daughter. He would’ve spared the young man. But one day, he suddenly thought that the young man could still be saved. He only hoped that whatever secrets the world of spirits held, Miguel would be able to bear them. So at last, Juanito agreed to help Miguel see the world of spirits.

Juanito opened Miguel’s eyes, and so it thus happened. Miguel saw the entire world where Sita belonged. He saw the time of legs and feet at the same time as the time of eyes. The air crackled with bullets chasing legs. The laughter of Gloria’s perpetrators wafted to the blue sky. The rustling of the leaves recalled the sound of feet on the hallways of Lourdes College. Sita’s cries just before her father hit her rang and rang, calling the Japanese to end her life as early as now. Miguel saw the passage of entangled legends. Hearts forcefully kept together and kept apart by the earth that cradled the heads that fell from their bodies by sunrise, leading to days wasted away in search of memories of a worshipped mother, around the cemetery in front of a school that just couldn’t be left behind by a lost spirit, whom a young man couldn’t talk to, who just wanted to understand and so fell into madness because believed by the people of Sagrada to have been played with by an old man, who lived all his life, and would go on to live for the rest of his life, alone—all this, and many more stories that evoked the rest of the body: hands covering bleeding ears, backs that couldn’t flee from whippings, sexes shat on, necks strangled by ropes, noses long numbed by the smell of corpses rotting—Miguel saw severed bodies of millions of people sprawled as far as where the sky and land met, both tainted red by rivers of blood flooding from the hearts of the countless corpses, rotting. In a flash, he saw how time has seeped into legends, which would then give birth to legends already ripe to birthing more legends.

In the face of all this, Miguel understood the origin of all things in the town of Sagrada. It was then that words, which no one ever understood, began to come out of his mouth, because he was already of another world, a world where legends were already made even before the act of creation.

Legends are hard to trust. No one should, as no one could, take the blame. I also couldn’t trust the legend that the town of Sagrada has created to explain Miguel’s descent into madness. They couldn’t even quite explain the name of their own town. Once I asked them how the place got its name. There was nothing sacred about their town, they said. That, and how I wouldn’t find any legend about this name. That everything they told me then were simply stories.

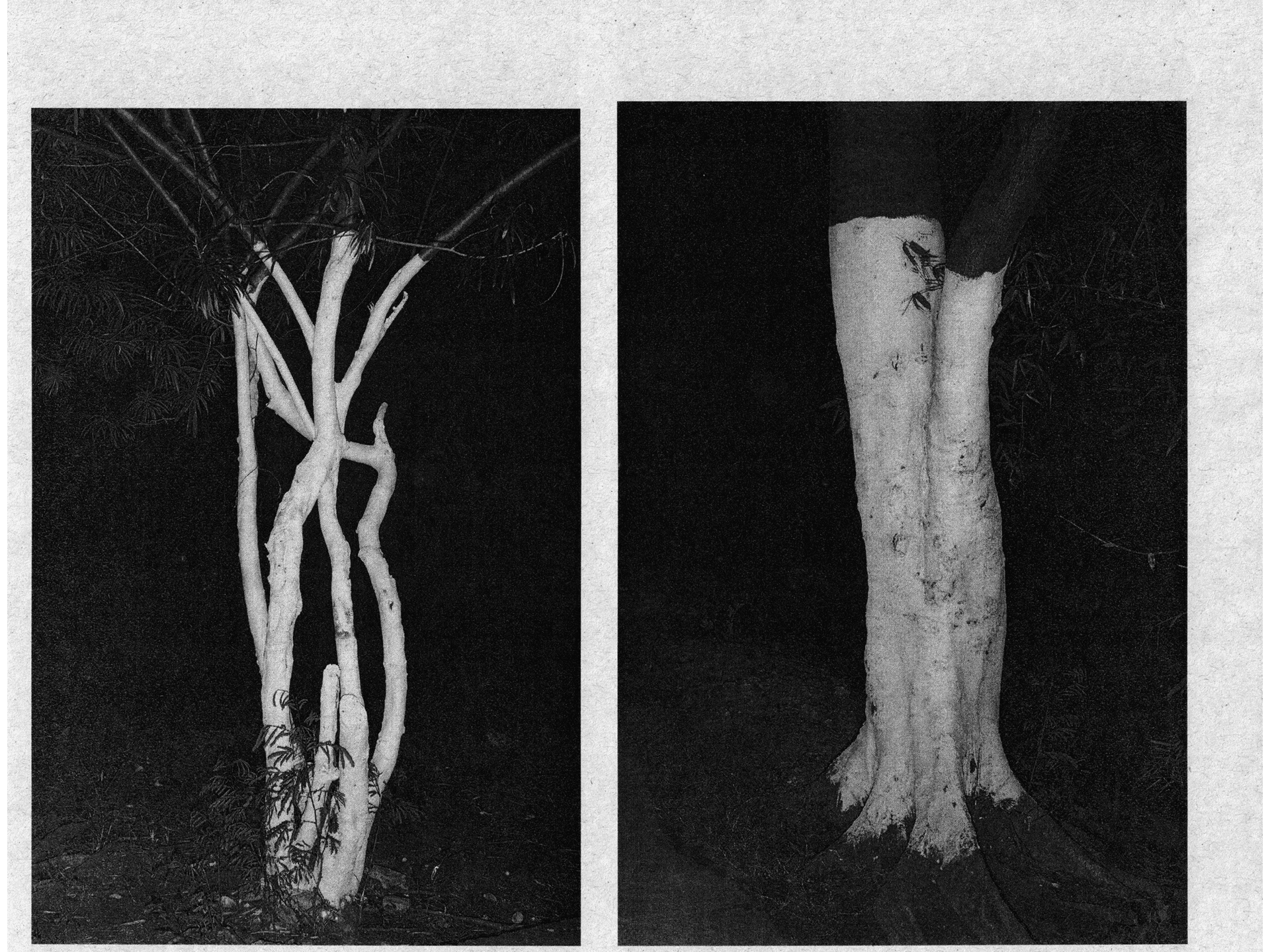

Mayo Naman Bagang Nag-bago Sa Libmanan (Nothing Has Changed In Libmanan), 2016

Outtake from Configurations series, 2016

Excerpt from Configurations series, 2016

Ang Kalayo Maski Gano Kasadit Nakakapaso Man Giraray (A Fire Still Burns Even If It Is Small)

/ A Wax Factory In Imus, 2017

Excerpt from Disinformation Express series, 2017

Excerpt from Disinformation Express series, 2017

Alvin Yapan is a writer of fiction in Filipino, with works including the historical novel Ang Sandali ng mga Mata (Time of the Eye, 2006) and short story collection Sangkatauhan Sangkahayupan (Humanity Bestiary, 2016), both of which won the Philippine National Book Award. His novel Sambahin ang Katawan (2011) was translated into English by Randy Bustamante and published by Penguin SEA as Worship the Body in 2024. He also recently published his research on folk aesthetics, Ang Bisa ng Pag-uulit sa Katutubong Panitikan (The Efficacy of Repetition in Folk Literature, 2023), which won the Philippine National Book Award for literary criticism and cultural studies. His research interests include the epic genre, folk aesthetics, and literature in the vernacular. He currently teaches Philippine literature at Ateneo de Manila University. He is also a filmmaker.

What role does the body play in this story—the hands, the feet, and the eyes that repeatedly recur in the storytelling?

It was Christian Jil Benitez who first noticed that a recurring narrative technique across all my fiction is my reliance on the synecdochic character of bodily parts. My second novel, Sambahin ang Katawan, makes this even more explicit. I use these as metonymic links between my characters and the ideas I want to convey. I thought this was an effective tool for readers to understand and, at the same time, feel in their own bodies what the characters were going through.

Do you have any personal rituals associated with your writing; what are they?

When I was writing “Mga Alamat sa Bayan ng Sagrada” and later the novel, Ang Sandali ng mga Mata, I would always have classical music playing in the background. I distinctly remember writing to Vivaldi’s Four Seasons and Beethoven’s Symphony No. 9. It was still cassette tapes back then. And sometimes, whenever I would pause, I would dance to the music just to keep the energy going.

Christian Jil R. Benitez is a Filipino scholar, poet, and translator. He teaches at the Ateneo de Manila University, where he earned his AB-MA in Filipino literature. He finished his PhD in comparative literature at Chulalongkorn University, Thailand. His critical and creative works have been published in various anthologies and journals, including eTropic, Kritika Kultura, and Here was Once the Sea: An Anthology of Southeast Asian Ecowriting. His first book Isang Dalumat ng Panahon (ADMU Press, 2022) received the Philippine National Book Award for literary criticism and cultural studies. His translation of Jaya Jacobo’s Arasahas: Poems from the Tropics (PAWA Press and Paloma Press, 2024) was a finalist in the 37th Lambda Literary Awards for transgender poetry. Most recently, he was among the winners of the inaugural PEN Presents x International Booker Prize for his translation of Alvin Yapan’s Time of the Eye.

What do you think has been lost and what has been gained between these particular Tagalog-English translations?

Sound, with its affective force, is the crucial difference between the Filipino original and the English translation. And yet, I’d like to think that the music of the former was not necessarily lost in the translation, and instead only inevitably transformed. While Yapan’s works, especially Sandali ng Mga Mata (2006) and its earlier version “Mga Alamat sa Bayan ng Sagrada” (1998), are often rooted in specific cultural contexts, they nevertheless remain translatable, often hinging less on particular terms in Filipino than on certain images, which can be rendered in another language. Because of this I feel that there is much to gain, not only for the Philippines but also, perhaps more so, for the world beyond it, in translating Yapan’s work—a wager that is, of course, premised on the commitment to an utmost care for language in the process of translation.

Can you tell us a little bit about your personal process within your practice of translation? Do you work on feel and intuition primarily, like a sculptor feeling through a form, or do you rely on certain formal tools to guide you through decisions?

Filipino languages are predominantly onomatopoeic: what words intend to mean is almost always conveyed through their very sound. In Filipino, it is also possible to seamlessly move between different temporalities and frames of thought, as well as to extend a sentence indefinitely, if not ad infinitum. So, when I render a Filipino text to English, I especially take care with the sound of the translation in order to compose music in the latter, which despite not being a close approximation to that of the original, would nevertheless sing on its own. At the same time, I am also careful to heed the sense of order in the English language, as manifested, for example, in verb tenses: almost every time I translate to English, I have to disentangle the contemporaneity of actions in the original Filipino to adapt to the rigidity of time in English. So, as much as I prioritize sound, I also adhere to the sense of order inherent in the English language. Or at least, for now. I still dream, and probably will always dream, of a time when the Anglophone world could be less dismissive, or at least more forgiving, of other forms of English. In, at, on, for instance—everything’s sa in Filipino.

Czar Kristoff J.P. is an artist whose practice spans photography, design, publishing, and pedagogy. He is currently interested in mapping the shadows of Filipino colonial history and migration scars. Cottage-industry publishing and other low-fidelity printing methods are his primary material realm.

His work has been exhibited at institutions such as Stedelijk Museum (NL), Foam Fotografiemuseum (NL), BAK basis voor actuele kunst (NL), Nieuwe Instituut (NL), Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation (DE), Jogja National Museum (ID), Tai Kwun Contemporary (HK), Bangkok Art and Culture Center (TH), Cultural Center of the Philippines (PH), Ateneo Art Gallery (PH) and Vargas Museum (PH) to name a few. He has received the Foam Talent Award (2022, NL), Thirteen Artists Award (2021, PH), and Ateneo Art Award (2017, PH).

He is the founder and housekeeper of pook aralan unrelearning, a migratory school interested in queering the culture and knowledge production in the Philippines.

How does the concept of translation figure in your practice? I am thinking, for example, of your use of low-fidelity printing methods, which makes clear the physical marks of conversion/transmission.

Timelines have always been illustrated as horizontal, but in reality, timelines consist of multitudes of lines, dots, dashes, curves, and clouds. Throughout our history, a lot of stories from the margins (where I am originally from) have been omitted, destroyed, altered, and forgotten due to the wrath of nature and by the most violent yet the most preventable man-made “calamities” such as colonialism, imperialism, capitalism.

In my practice, I try to understand and make sense of these routes. The monuments of transitions and rerouting, such as footnotes, gestures, movements, feelings, friendships, hymns, cries, questions that arise in between point A to point/s B to Z, become guides in navigating this route, which I think are important to be archived, distributed, to be talked about in public spaces—to give light, to heal wounds.

The ums and pauses whenever we try to speak in English are often seen as a weakness, as imperfections by many. Translation takes a lot of labor and as I become older, I realize that translations will never be perfect, are not meant to be perfect. Clarity doesn’t always quantify the truth. Sometimes, it is the blurred grains and the unstructured that ground us and reveal the depths of history.

How does Bicol, or Laguna, or your sense of home feature in these works?

When I received the email, I was actually on the bus on my way home to Laguna. I read the text immediately—first the original version then the English translation. I highlighted some phrases that I find moving such as “. . . sa hanging walang sinumang nagtatangkang sumagap,” “Iniipon niya ang mga tuyong dahon sa bakuran ng kolehiyo, saka sinisigaan,” “. . . talahib na walang tigil sa pagyuko’t pagsamba. . . ,” “. . . nilalanguyan ng mga isdang napakagagara ng palikpik at napakatitingkad ng kulay ngunit hindi naman napakikinabangan bilang pagkain,” “. . . felt numbed the pain when he moved his hands toward the flame,” “Until he tripped and fell into a puddle of mud where carabaos bathed,” “For the first time, the sunrise didn’t promise hope but death.”

While reading the text, I thought of my hometowns in Bicol/Camarines Sur, where I was born and raised, and in Laguna, where I spent my late teens and early adulthood. There are some parts that seem familiar, not only how the landscapes were described, but the anguish of every character—some kind of power to reshape or create new planes, as a way of survival.

The selection of images was photographed in 2016, 2017, and 2025, in various places such as Laguna, Cavite, Camarines Sur, and Muntinlupa City. Images of accidents, excursions, ruins, and markings.